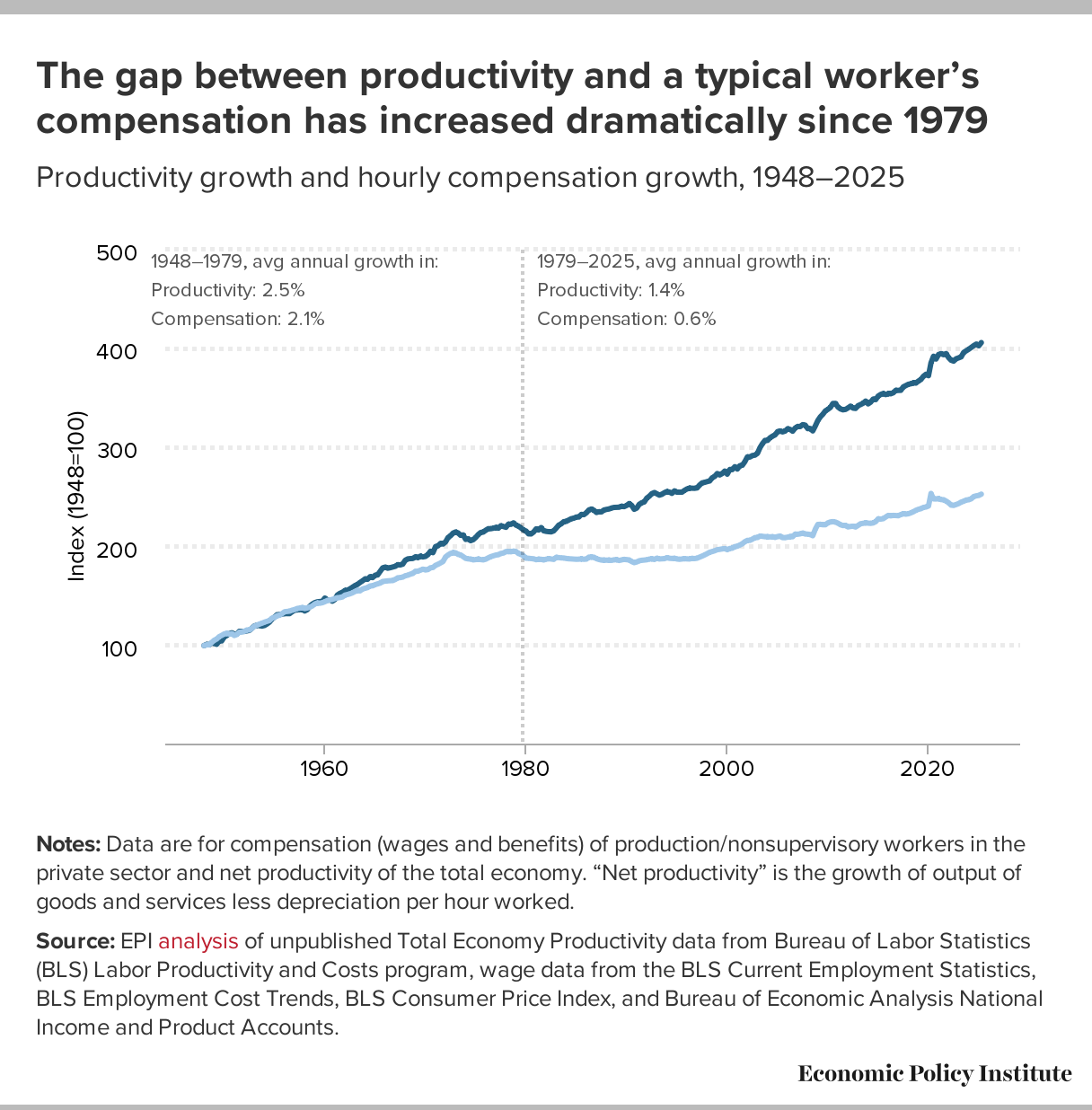

Economic Policy Institute has recently updated their Productivity-Pay Tracker and it points to continued divergence between increase in productivity and increase in wages.

But it is not as straight-forward as it looks!

Ideally, an increase in labor productivity should be paired with an increase in wages. However, it IS possible for productivity to rise without any change in labor productivity. How?

At the risk of oversimplification, imagine a simple bread bakery.

Its output relies on various types of labor: skilled bakers and support group ( sales, cleaning, accounts and others). Now, imagine this bakery buys an automated bread-making machine. The machine takes dough, presses a button, and produces perfect loaves.

In this new setup, the bakery still needs the support group, but instead of skilled bakers, they only need a low-cost attendant to operate the machine. The machine itself requires maintenance, which is outsourced, creating new jobs at the machine's manufacturing company.

Fewer people are now needed to produce the same volume of bread. These workers, as a group, may receive a smaller share of the bakery's sales, but since there are fewer of them, they might individually earn more. This is an example of a higher-order economy of scale at play.

The specialized knowledge of the bread-machine makers is highly valuable and commands higher returns. This process can be repeated, leading to gains accumulating with those who possess unique knowledge. For instance, the consulting baker at the bread machine factory would earn far more than an average baker.

So this productivity gain has now created inequality.

We have a super-well-paid consulting baker and many attendants in various bakeries for operating the machines and machine maintenance workers.

Our bakery saw deployment of capital that increased its productivity but also changed the employment profile of the operation. This shift, where technology increases production's capital intensity, leads to a polarization of incomes. On one hand, it amplifies the scale and returns for those with distinctive knowledge - like our consulting baker. On the other hand, it reduces the skill level required for many jobs, consequently lowering the expected income for those working in these jobs.

This change represents a structural shift from an effort-based society to a knowledge-based society. Consequently, those without a college degree or the ability to do "knowledge work" may experience stagnant wages. In this new society, the value of physical effort is reduced, leading to lower pay for jobs that require it.

New Metrics for a New Economy

To truly understand productivity and income changes, we need new concepts. We could measure the "wage content of a job," which would track the wage changes for a standard basket of jobs, similar to how we track a consumption basket for inflation.

Conversely, the "job content of a wage" would measure the value of work that a specific wage can accomplish over time. Measuring these factors would give us a clearer picture of the ongoing economic shifts.

Ultimately, a country's job-profile, and knowledge profile should align with income-profile. If they do, it suggests that capitalism is functioning as it should. In other words, a country with say few doctors and many

I discuss some of these concepts in my book "Subverting Capitalism and Democracy".